Key Takeaways

- If GNOME became its own operating system, that would simplify the Linux experience for many newcomers.

- GNOME OS could provide a more consistent interface and app experience.

- A dedicated GNOME OS could streamline press, advertising, documentation, and app development for the GNOME platform.

I’ve used Linux on and off for years. Most of that time I’ve used GNOME, and I have even primarily used GNOME apps. For simplicity’s sake, I wish I could just tell people I use GNOME, not Linux. I’d love to see GNOME OS become its own thing.

First: What Is GNOME, and Is It Linux?

When you first come across Linux, it’s often a surprise that there is no one thing called Linux. Technically, now that I mainly use Samsung DeX, I’m still a Linux user. Those years I rocked the OG Chromebook Pixel? Still a Linux user. Yet neither of those things are what come to mind when people say they use Linux.

Rather, they mean a Linux distribution, or distro. Linux is just the kernel, the bit that enables something to happen when you press a button on your keyboard, enables pixels to appear when you turn on a monitor, and empowers your modem to connect to the internet. It’s the part that’s invisible, that most of us have no reason to ever think of.

The parts we actually see? Those are desktop environments and applications, and they look wildly different from one another. GNOME is one of these desktop environments. KDE Plasma is another (some would say better). These two look as different from one another as macOS does from Windows, yet they’re both Linux—and if you’re having a hard time following this, I don’t blame you. It’s a lot to type, and it’s even more to casually explain to someone in person when I’m just trying to connect my laptop to their projector, and they ask what software I’m using.

That’s why when a GNOME developer writes a blog post proposing that GNOME become a general purpose operating system, I’m here for it.

The Linux Distro Model Is Dated and Confusing

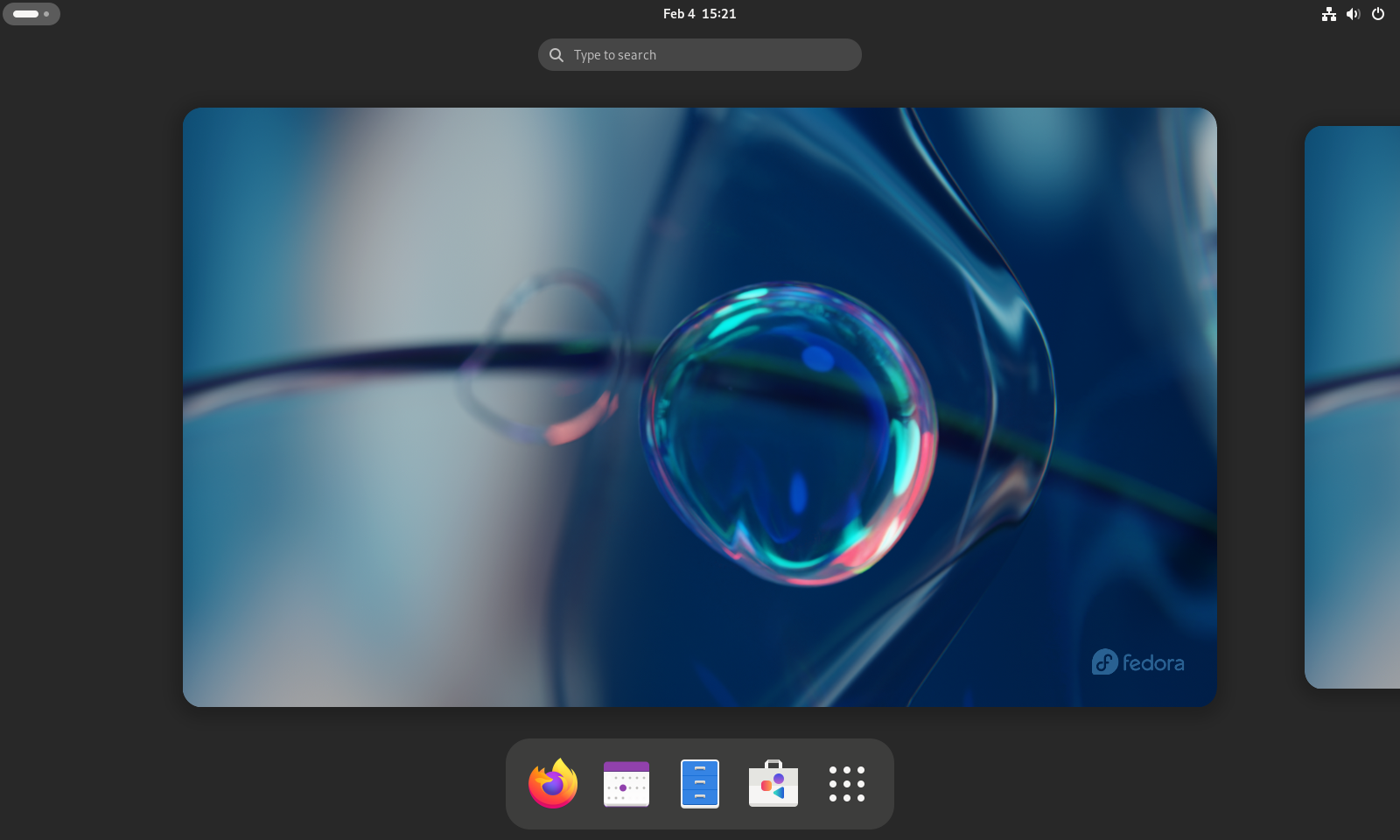

For years, I turned to Fedora Silverblue as my go-to Linux distro of choice. It behaves as close as I would expect a GNOME OS to function. It provides a near-vanilla GNOME desktop, with mostly GNOME apps and an app store that functions mostly as GNOME developers intend. Many GNOME developers are also Fedora developers, after all.

Silverblue is an immutable, more stable version of Fedora. Combined with the Flatpak app packaging format and the Flathub app store, the experience feels akin to using a smartphone. Apps are easy to find, they’re easy to install, and they even have a degree of sandboxing.

The thing is, Silverblue is a niche within a niche. If you’re here for a pure GNOME experience, first you discover GNOME, then you discover Fedora, then you discover this alternative version of Fedora. GNOME is such an easy-to-use computer interface, but no part of discovering it is friendly to the people who would probably like it most.

It Wouldn’t Be Your Standard Linux Distro

Long-time Linux users may understandably reject the idea of creating an official GNOME OS as a solution. There are already too many distros, they would argue, and so creating yet another seems counterproductive. Still, certain distros feel separate from the rest. SteamOS, on the surface, is just another generic KDE Plasma distro, but because it ships on the Steam Deck, I can mention it to a certain type of computer user, and they immediately know what I’m referring to.

GNOME OS has the potential to reach a similar recognizability but for a different reason. GNOME OS would offer a consistency between what the distro is called, the desktop people see on-screen, the apps that come pre-installed, and the places you go to find it all. If I tell someone I use GNOME, I can point them to GNOME.org knowing they can install the same thing without having to come back to me asking which distro from the list of GNOME distros is the best way to try GNOME out.

In a sense, this is the beauty of elementary OS. It’s the clarity of vision and presentation that attracted me to elementary OS more than anything else.

Unfortunately, the development team is too small, and the number of available apps too few, for me to stick with that distro. GNOME, however, already does most of what I want. It’s just muddied up by having its identity mixed with Ubuntu or Fedora, who both are and aren’t trying to be GNOME.

You’d Get a More Consistent Experience

Ubuntu was my first Linux distro (technically Xubuntu, but not for long). The distro lost me as it branched further into creating its own visual identity. Now Ubuntu ships a version of GNOME that has its own custom theme and patches intended to make GNOME feel like Ubuntu’s former Unity interface. Ubuntu also applies desktop icons when GNOME explicitly doesn’t.

Apps on Ubuntu have a minimize, maximize, and close button, whereas GNOME doesn’t—just check out the screenshots of these GNOME apps I recommend to see what I mean. Even this small difference means some apps look awkward on Ubuntu unlike on standard GNOME. More glaring issues can arise from the use of a different theme, causing some developers to request that distros not theme their apps. Ubuntu also includes some non-GNOME apps and designs some of its own software with a different vibe.

This all creates inconsistencies that I understand but wouldn’t expect newcomers who aren’t steeped in Linux lore to get.

Even distros with more consistency, like Fedora, still have app stores that recommend software made for different desktop environments. Users have to navigate why apps behave differently when they come in different formats, with a Firefox RPM behaving differently from a Fedora Flatpak, which also behaves differently from a Flatpak from Flathub.

A GNOME OS would presumably ship only the GNOME interface and apps, themed the way app developers expect. GNOME’s app store could also do a better job differentiating between software made for GNOME and everything else, much like the elementaryOS AppCenter does.

This Simplifies Press, Advertising, and Documentation

I would hope that GNOME OS gets top placement on the GNOME website. When someone asks what GNOME is, they can go to GNOME.org, read about GNOME, click a download button, and follow the instructions. They can use any of the first-party GNOME apps they see over at apps.gnome.org. They can be directed to Flathub for anything else.

When they run into issues, they can head back to the GNOME website and find documentation specific to GNOME OS. They don’t have to navigate why app installation instructions differ between Fedora, Ubuntu, or openSUSE.

GNOME app developers have a clear platform to target and consistent guidelines to follow. They can release videos for their apps running on GNOME OS and point users in that direction, even if Flathub remains the place people go to for the download link.

GNOME can continue to be available as an option from any of the traditional Linux distros for the people who already know and love them, but it would be far more accessible to the legions that don’t.

KDE Neon is the closest thing to a GNOME OS on the KDE Plasma side of things. Neon’s creation was initially controversial, but this many years on, it hasn’t been a big deal. KDE Neon’s existence did nothing to stop Valve from using KDE Plasma for SteamOS. No one’s freedoms are restricted by having an option that a desktop environment is directly invested in.

Yet KDE Neon feels like a half measure, something with an awkward name that is ultimately still just Ubuntu with a different face (which may be part of the reason there was chatter at this year’s KDE developer conference for KDE to have a complete OS of its own). I hope GNOME creates something like KDE Neon, except if they do, I’d like them to fully commit to the bit.