When faced with acid-dripping aliens, an untested machine that travels through wormholes, or a space station shattered by hurtling debris, it is the tough female astronaut who steps up to save the day.

And perhaps Hollywood is on to something. A major study into the impact of spaceflight suggests women may be more resilient than men to the stresses of space, and recover more quickly when they return to Earth.

The findings are preliminary, not least because so few female astronauts have been studied, but if the trend is confirmed, it could prove important for astronaut recovery programmes and selecting crews for future missions to the moon and beyond.

“Males appear to be more affected by spaceflight for almost all cell types and metrics,” scientists write in a Nature Communications paper that examines the effects of space travel on the human immune system.

Led by Christopher Mason, a professor of physiology at Weill Cornell Medicine in New York, a team of researchers examined how the immune system reacted to space flight in two men and two women who flew around Earth as civilians on the SpaceX Inspiration4 mission in 2021, and compared the findings with data from 64 other astronauts.

The study showed that gene activity was more disrupted in men than women and took longer to return to normal in men once back on terra firma. One protein affected was fibrinogen, which is crucial for blood clotting.

“The aggregate data thus far indicates that the gene regulatory and immune response to space flight is more sensitive in males,” the scientists write. “More studies will be needed to confirm these trends, but such results can have implications for recovery times and possibly crew selection, for example more females, for high-altitude, lunar, and deep space missions.”

It is unclear why women might be more resilient to spaceflight than men, but Mason said being able to cope with the demands of pregnancy might help. “Being able to tolerate large changes in physiology and fluid dynamics may be great for being able to manage pregnancy but also manage the stress of spaceflight at a physiological level,” he said.

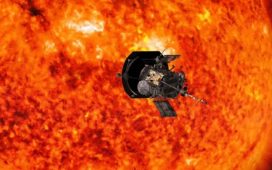

The paper is among more than a dozen published on Tuesday that analyse samples from the Inspiration4 mission crew and other astronauts who spent six months or a year on the International Space Station. The measurements lay the foundations for a space biology database that will be used to reduce the health risks for future astronauts bound for the moon, lunar orbit and potentially even Mars.

Nasa wants to fly humans around the red planet as early as the 2030s, but another study published in Nature Communications raises serious doubts over the safety of such a long, deep space mission. The international team, led by researchers at University College London, exposed mice to simulated galactic cosmic rays (GCRs) and found that the dose humans might encounter on a round-trip to Mars could cause permanent kidney damage, with astronauts potentially needing dialysis on the return leg if they were not protected from the rays.

Keith Siew, a research fellow in renal medicine at UCL, said the kidneys were extremely sensitive to radiation, but that permanent damage may not be obvious for months after exposure. The radiation appears to damage mitochondria, the tiny power plants inside cells, which could ultimately contribute to kidney failure.

“It’s likely to be a serious issue,” said Stephen Walsh, professor of nephrology at UCL and a senior author on the study. One problem with GCRs is that shielding can make matters worse, because the incoming rays are so energetic they produce secondary radiation that also harms astronauts. “It’s very hard to see how that’s going to be OK,” he said.